“DIY”

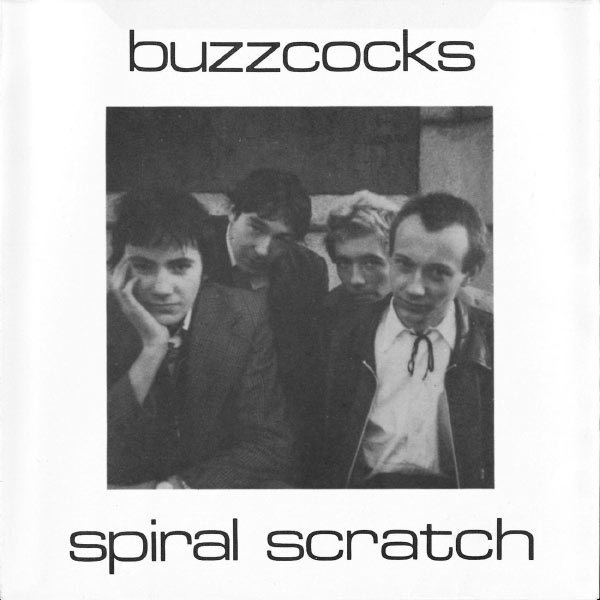

For those who don’t recognize the album above, or for those who do but are wondering why there’s a picture of a seminal punk record on a blog dedicated to post-rock, I’ll give a short summary of its significance. Back in 1977, the Buzzcocks self-recorded and self-released their debut album, Spiral Scratch. Completely on their own, with no major label support.

You might be saying to yourself, “So what? My pothead cousin does that in his bedroom with a cracked version of Ableton and the mic on his Macbook.” Well, good for him. I’m sure his parents are just oh so proud. But this is not 1977. In 1977 Ableton wasn’t around, and when you said the word “apple” there was no confusion as to whether you were talking about a fruit or not.

I’ll spare you the long history lecture and summarize as best I can. This was the first record that truly challenged the notions that a band needed a major record label with support from distribution companies to put out a successful record, and in doing so, set the precedent for what would eventually become today’s DIY music scene. The Buzzcocks paid for Spiral Scratch‘s recording, mixing, initial pressing, and release with the support of £600 loaned to them from their family and close friends.

Fuck yeah, stick it to the man. Keep it within the scene. Us against them. The Buzzcocks would never just ask for a handout from total strangers, and would absolutely scoff at the idea of today’s bands “crowd-sourcing” or “crowd-funding” their records on the internet… right?

…right?

(If you want the non-summarized history of Spiral Scratch, as well as the rest of the post-punk movement, I highly recommend you pick up Rip It Up And Start Again: Postpunk 1978 - 1984 by Simon Reynolds.)

Growing up and coming of age as an impressionable teenager in the re-re-emerging skate culture of the late 90’s and early 00’s, many of my predispositions and initial hostility toward crowd-funding sites and those who choose to use them stem from the overwhelmingly anti-establishment mentality prevalent (though admittedly dwindling, by that point) within the very punk influenced skateboarding community. The community was there to serve itself, because no one else would. If you wanted to get something accomplished, you did it yourself, with the help of your close friends. These were basically mantras me and my friends lived by, be it building a mini ramp in someone’s backyard or putting out a record.

But it is also not 1999 anymore. It’s been 15 years since Tony Hawk landed the 900. He’s 46 years-old now. Three people have landed freaking 1080’s since then, including a 12 year-old.

The issue at the core of this thought piece is how things have changed, and how some attitudes (including my own) are slow to catch up.

So here it is: Let’s talk about what it means now to “Do It Yourself”.

.

In an early email to Jurģis Narvils of the band Audrey Fall, I told him my opinion on bands who rely on crowd funding sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo. I said, “It comes off as begging.” Was I right to say that? To imply that a band should limit their possible avenues of financial support? For what reasons? To save face? To uphold some righteous standard maintaining that the only honest way for a band to promote and further themselves is to put in the years of practicing, hazardous touring, shitty day jobs, and wallet draining studio time? I’m not so sure anymore…

If you feel passionate enough about something, doesn’t it make sense to put yourself out there and use every single tool at your disposal to make that something happen? Hell, musicians still go out on the sidewalks to play their music to the public, stereotypical open guitar cases and all. You can see it yourself walking up and down Wabasha in downtown St. Paul when the weather is nice.

So is that what this whole crowd-funding thing is? Is this the modern day equivalent of busking on a street corner? I guess that’s a fair comparison, except personally I’m much more likely to give money to a man playing live on the sidewalk than a prerecorded YouTube video. Then again, by using a crowd funding site you are casting a much wider net, and (one would think) more likely to come in contact with people both more able and willing to part with some of their cash to support a stranger’s cause.

But is that really an accurate, or even fair comparison? I asked Jurģis what his own thoughts were, and whether Audrey Fall had considered, or would ever consider using the crowd-funding model. He responded saying:

“Well, a few people have suggested that we try to crowd fund a vinyl release, but we’re not really interested in that kind of thing. And I’m 100% certain that we wouldn’t get the money needed for that anyway. It might work for bigger bands that have a steady fan base, but we basically came out of nowhere and got a bit of hype going on, but other than that I don’t think we’ve made a momentum big enough to make a campaign of any sort. If we get a more steady fan base and want to remain independent and unsigned, then probably it would be the best way for us to release the second album, perhaps including some other merchandise. I view it simply as a pre-order. There’s no use for it until you get demand big enough for it.”

Somehow, that angle had never occurred to me. A pre-order?

It’s become fairly common practice for bands to apply “tier levels” for donations when utilizing crowd-funding sites. $5 gets you a thank you in the liner notes. $10 gets you a poster. $15 gets you a T-shirt and a poster. $1,000 and you get all of the above mentioned swag and they’ll play at your kid’s bar mitzvah. Etc…

By giving fans something right off the bat with a donation, bands who crowd-source their activities are adding an incentive that ruins the whole previously mentioned, “gigantic-world-spanning-open-guitar-case” metaphor. I don’t know many buskers that sell t-shirts. I know even fewer who play bar mitvahs.

As also pointed out by Jurģis, the question seems to be not so much if bands who wish to forego label support and remain unsigned should consider the crowd-funding model, but when. But what about a band that has some label support? I asked Rocket Miner, (currently on Shunu Records) what they thought about bands using crowd-funding websites, and whether they’ve considered it…

“Crowd-funding websites seem to be the norm these days with many bands, and the whole DIY way of getting things accomplished. We have considered doing some of those sites but we feel we are still a fairly new band, so we are going to try to fill out our fan base and things a bit further, and then maybe try one in the future if need be.”

So… when? At what point should a band decide to start a campaign to finance their activities? What’s the benchmark for this kind of thing? Do we go by Facebook likes? At the time I first listened to Audrey Fall they were sitting around 2,200 likes. That’s a healthy amount of likes for a band that just released their first record. As of the time I’m writing this sentence, they’re up to 2,810 likes. As I’m typing this sentence, Rocket Miner has 1,222 likes. They both have overwhelmingly positive reviews for their latest albums on Postrockstar. (Audrey Fall’s here. Rocket Miner’s here.) That’s 2,810 and 1,222 people, respectively, plus the entire readership of what is arguably the most well known post-rock related site (aside from the Post-rock Facebook page) out there that they could directly ask to support a fundraising campaign. However, both bands feel like they wouldn’t have enough support to justify using a crowd-funding site (yet). Ultimately, I think the question of “when” is subjective to each band and their specific goals.

So that’s crowd-funding from a band’s perspective, but there is another perspective I feel is still very important that I haven’t heard from. Whether you love them or hate them, both major and independent record labels are an integral part of the music industry. They have been and most likely will be for a good long while. So is crowd-sourcing a threat to them? I’ll explain.

Without going too in depth, there are a lot of slightly underhanded and shady, but completely legal, dealings involved with major (and certain less than reputable independent) label contracts. A very dumbed down and summarized version is that every single cent a label spends on a band in any way, from recording, touring, merch, music videos, and even time and money spent by executives while “networking and pursuing further business opportunities for the artist” (sometimes without the band’s knowledge), are put into accounts that (you can probably see where this is going) the artist must eventually pay for. These are called “recoupable costs”. This, and several other ways are how major labels can, and have, taken advantage of starry-eyed musicians who don’t speak Legalese. To call it indentured servitude would be more than a tad hyperbolic, but to some artists, it may seem that way when they see how much money they suddenly owe a label after their first release comes out, or their first tour. So does crowd-sourcing undermine a major label’s ability to keep an artist indebted to them? Or somehow threaten them with becoming obsolete?

Honestly, I doubt it.

These are billion dollar Goliaths which have been around for decades in some incarnation or another. And not to climb too far up on my hipster pedestal, their goal is churning out music as a product with as much broad ranging appeal as possible, to be sold for mass consumption. Before you mock my Chuck Taylor’s and respectable vinyl collection of bands most people have never heard of, I’d like you to read this NPR article (oh, the irony) on how much money Def Jam spent on one Rihanna song. Then you can rip on the Chucks.

Perhaps a more important point of consideration, however, is how relevant those “major” labels really are to such a niche genre as post-rock/post-metal. Off the top of my head I can’t think of any major bands in the genre that are, or ever were, on any of the major labels. Looking through my collection of music that isn’t self-released, the names I see are Sargent House, Temporary Residence Ltd., Hydra Head (I miss you, Isis…), Constellation, Deep Elm, Southern Lord, Translation Loss, Neurot, etc. Not an Island Def Jam, Interscope, or Atlantic in sight. So let’s ask a label that’s relevant.

(Not off the top of my head: Sigur Ros left Fat Cat Records to sign with EMI before the release of Takk… in 2005. And there’s some debate as to whether Sub Pop, home of Earth before they signed to Southern Lord in 2004 as well as the current North American distribution arm for Mogwai, can still be considered fully “independent” after 49% of the company was sold to Warner Music Group in 1995.)

I decided to ask Deep Elm Records. For those who aren’t familiar, they are an independent label started in 1995 and are one of the more post-rock friendly independent labels out there. Some bands on their roster include Lights & Motion, Moonlit Sailor (which was the first band I reviewed for this blog), and The Appleseed Cast. I chose to ask Deep Elm not only because of their staunchly independent (DIY) nature, but for their very progressive attitude and willingness to change things up in an industry which tries so hard to maintain the dying economic models of decades past. Recently they made their entire catalog (that’s 200+ albums) available for download at a “Name Your Own Price” option. Like I said, progressive. If there’s a label that knows the inherent value of being able to adapt, it’s them. Here is what they had to say about bands utilizing crowd-funding sites:

“…We’re a huge advocate. Since the grand majority of music is being downloaded / streamed for free, we think it’s only fair to ask fans to support the bands they love by contributing what they can to the creation of new music, videos, tours, etc. It makes fans part of the process and I think gives you a great feeling when you see the final result of the project at hand. It’s a very satisfying feeling. We also think it’s important for fans to get an idea of what goes into the production of an album / video. It’s very costly! Most often crowd-funding campaigns only help offset a portion of the overall costs. In this day an age, we really need to work together to keep the indies alive. Together we stand, divided we fall.”

Admittedly, Deep Elm is a unique label with a set of values that in all likelihood don’t line up with those you’d find at a giant label like Warner or Virgin. However, that doesn’t change the validity of their statement. Post-rock as a genre doesn’t have major label support. It’s still a niche genre and I’d wager it will continue to be for the foreseeable future. This means any label support comes from labels who are willing to risk investing in a comparatively small portion of the entire music market. And those are the indie labels. They can’t afford to spend $1,078,000 to write one song.

While it would be naive to say that indie labels don’t care about the money, they genuinely do care about the music and are there to support the bands they sign. So with the traditional model of record sales supporting the artist being a thing of the past, and royalties from things like mainstream radio play being, for the most part, non-existent (name the last time you heard This Will Destroy You on heavy rotation at your local rock station…), bands on smaller independent labels who choose to crowd-fund their releases and studio time are lessening the financial burden of both themselves and their label. Pre-orders are filled and already paid for. Fan/artist interaction is increased, which in turn generates more interest and more returns. And some lucky kid out there gets a totally bitchin’ bar mitzvah.

So where does all this leave me on the issue…?

To be completely honest, before I started writing this piece, I was admittedly and openly against bands which chose to use crowd-sourcing to fund anything they did. While sketching out the rough draft, I actually had an entirely different conclusion half-written where I stated that I was “still up in the air” on the issue. To keep that as the final note to this piece, which is hands down the most ambitious and time consuming I’ve ever written, would be to throw away all of the time I spent emailing bands (and a label). More importantly, though, it would be throwing away all of time they took to get back to some random person on the internet with their input. Doing so would make this piece a complete waste of my, their, and your time.

So I’ll just come out and say it: I was wrong.

I was wrong to call it “begging”. Most bands worth anyone’s time fully understand that to utilize the crowd-funding model effectively, there must first be a crowd. More importantly, however, that crowd must already be engaged. People don’t simply throw money at you for putting your demo up on Bandcamp. Certainly not enough for you to get anything important accomplished. Bands which have that engaged crowd have reached that point because they’ve already put in so much work the old fashioned way: By playing tons of shows, working those shitty day jobs so they can spend their free time and money to get quality recordings, and in general just not sucking. “Doing It Themselves”, if you want to tie a nice bow on it.

Crowd-sourcing your activities as a band/artist is fine. Hearing from so many different perspectives has completely changed my mind. And if all of that wasn’t enough, as a last and final nail in the coffin for my antiquated, misinformed, high horse-riding, anti-establishment, “punk” mentality…

Completely unbeknownst to me, the Buzzcocks released their ninth studio album, The Way, less than two months ago (which is, by some unfairly strange and aggravating coincidence, about the same time I started writing this piece)…

…and it was completely crowd-funded.

I guess it’s time for me to grow up, too.

.

An enormous thank you to Audrey Fall, Rocket Miner, and John at Deep Elm Records for their invaluable contributions to this piece, and taking the time out of their lives to get back to some random person on the internet. I sincerely appreciate it, and thank you again.

.

If you enjoyed reading this piece, you may still absolutely hate something else I’ve written. Better safe than sorry. Click here to see all of my Advice, Stories, and Complaints, and find out whether or not we’re compatible as soulmates.